Bronze, oil paint 16 x 24 x 12.5 cm (6.3 x 9.4 x 4.9 in.) Unique

SOLDHamish Pearch (b. 1993) is a British artist living and working in London. Half of the sale proceeds from five new bronze sculptures will go directly to Chefs in Schools.

Chefs in Schools is revolutionizing school food across the UK. Since 2018, the charity has been training school chefs to cook delicious, nutritious meals from scratch, ensuring over 100,000 children have access to quality food every day. Beyond the kitchen, Chefs in Schools educates pupils about nutrition and instils a lifelong understanding of how to eat healthily.

“In my work of late, l've been thinking a lot about roots and branches, beginnings and destinations, cut backs, shortcuts and the long way round. How things are held, nurtured or let off the leash to do their own thing in a shaded corner. I was drawn to Chefs in Schools because it feels so vital to nurture an aspect of growing up that is, or was, at least in my experience, largely forgotten about: food. I think it's important we view nutrition as a universal fundamental bedrock upon which fertile soils can grow.” Hamish Pearch.

"Build your own paper city", for Hospital Rooms’ Digital Art School

"Build your own paper city", for Hospital Rooms’ Digital Art School. Whilst the programme is specifically crafted to function within mental health hospitals, it is also freely accessible to the general public.

The project invites participants to construct a paper metropolis using downloadable, printable templates. From barns and hotels to residential structures, water towers, and a scattering of flora and fungi, each sculpture serves as a canvas for personal interpretation and creative interventions.

Hospital Rooms is an arts and mental health charity that brings art and creative activity to people who are in contact with mental health services. The Digital Art School is a free national art programme for every mental health inpatient ward in England.

The Digital Art School has been developed over three years with people who have used mental health services ranging from Psychiatric Intensive Care, Acute, Mother and Baby, Forensic and D/deaf among others.

Hamish Pearch interviewed by Robert Frost for émergent magazine

Robert Frost One of the first works I ever saw of yours was an ice sculpture on the front step of Union Pacific. This was just last year, when Ted Targett curated Day by Day, Good Day, an exhibition conceived from a series of paintings made by German artist Peter Dreher from 1974 until his death in 2020. Unlike the other works on show, this sculpture no longer exists; did not and cannot pass the test of time. The icy tortoises, in my mind, illustrate wider insecurities and instabilities in yours. Is that correct?

Hamish pearch The thing I’ve always loved about sculpture is once you’ve looked at something from the front, by the time you’ve got round to the back you only have your memory to rely on to imagine the other side. It becomes a sort of patchwork of visual memories from split seconds ago.

To me, the tortoises were an experiment in speeding up the experience of objects and our relationship to them in time. How can I make this slow moving couple speed up into the time it takes for them to disappear? For them, at that time of year in London, it took about a day. There’s only a couple of minutes when they’re fresh out of the freezer and all the details are sharp, otherwise you’re looking at something quickly disappearing.

Like the Peter Dreher paintings, I wanted something to be re-established every day. I wanted to highlight minute differences in light, temperature, mood, feeling. Each night the work was recast in a rubber mould, and put out the front freshly formed when the gallery opened its shutters. It was placed outside by Ted or other members of the gallery team, but whatever time you arrived at the show, the work would look different.

We’re always passing from state to state – secure to insecure. Stable to unstable. For me, this feels real.

RF Did you make the atom-like structures at Ginny on Frederick with those same transitions in mind? They look like they could explode at any moment.

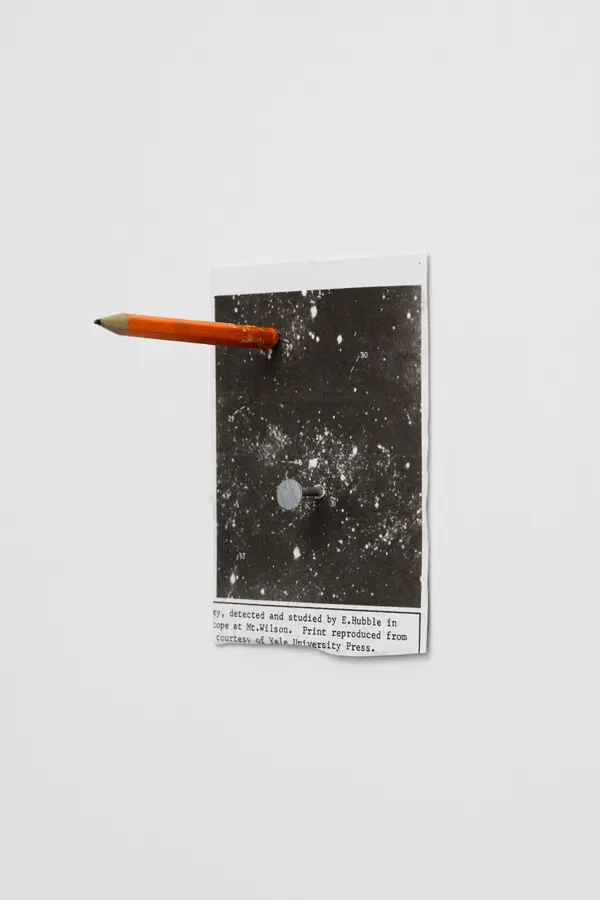

HP I’m interested in ideas around potential. There’s an amazing film (on YouTube) that Charles and Ray Eames made called The Power of 10. It starts with a couple having a picnic by the side of a lake. Every 10 seconds it zooms out, so you see the couple as part of a wider spatial context. Finally, it reaches the edge of the known universe – little floating dots. At that point we zoom back in, all the way back to the couple, and then continue into their skin and through cell structures until we reach atoms. I realised that the infinitely small and impossibly large look like each other. They are different, yet the same. The works in the show were solid painted bronze, resembling pens and pencils until very closely inspected, barely held together at their nibs, as a group like atoms, like a constellation. I like the idea that things could potentially be both opposites and identical at the same time.

RF Now I also see it another way: the way the sculptures occupied the space, set atop plinths of varying heights, served to illustrate, or enact, this interest of yours. At the same time as appearing as atoms, the display heightened the tensions between all the works, the architecture, and the audience; mimicking, to the extent of my knowledge, space. Feeding off the Eames film, Smoky, Moth and Mike stressed the limits of human understanding or perspective.

HP Yes. The title of that show and of the works in it were selected from the names we give to storms, bombs, suns, and galaxies. In the end, the names we assign to distinguish these things – whether it’s for natural phenomena, destructive forces, celestial bodies, or even artworks – fall short of these events. A name is a thing but it is also, in a way, a failed attempt at truly illustrating that thing.

RF I think Reilly Davidson summed it up by drawing a line between your ‘anthropomorphisation of natural phenomena’ and René Magritte’s 1927 essay ‘Les mots et les images’: “Although,“ she wrote, “the object (a wall) hints at other objects behind it, the totality of the scenario eludes comprehension.“ On other occasions, less accurate or forthright titles, such as Storage Wars, have carried as much, perhaps even more, weight.

HP I loved Reilly’s text. She also introduced me to ’The Petting Zoo’, which I hadn’t read before. I think working with writers and curators on projects as they unfold is so important for expanding what a thing can be. For the Schools Show, the key for everything in the room was the inside of a Big Yellow Self Storage door, which I fabricated from bits of old wood painted with gloss yellow and beige. I cut moth balls into half-spheres for the rivets. I imagined that the room was the inside of a self-storage unit. Everything was made with that in mind. The things in the room were a collection of objects from different geographies, scales, moments in time, manmade as well as natural. Some of sculptures within Storage Wars were models of water- towers that I had seen in the UK and Europe. Thinking about it now, The Power of 10 was probably in my mind then as well – the micro and the macro. Also in the room were sculptures of mushrooms growing, which share a formal resemblance to water towers. From an aerial perspective, if you were in a plane or if you were a bird, you can see how water towers in a landscape sprout up where needed. Mushrooms do a similar thing on a scale much closer to the ground. I like the idea that both these structures – mushrooms and buildings – can be foraged for, which, for me at the time, was about understanding scale through foraging.

RF: I feel this very much in your recent show at sans titre. Where we find oxidized mushrooms imitating planets. Salomé Burstein said the infinitesimal is felt as much as the cosmos. Can you talk about your relationship to nature, and specifically to foraging?

HP I think we have to question what ‘nature’ is, or whether it even exists. The philosopher Timothy Morton’s thinking has been instrumental in reframing how I perceive nature. In much part due to his work, I no longer subscribe to the assumption of separation between humanity and nature. We live in a dynamic, symbiotic system. Morton believes that all things are interdependent, and that everything in the universe has a kind of consciousness, everything from mushrooms to planets. I think that’s how we should frame our place in the world. My relationship to nature is completely intertwined. I call myself Hamish but my body contains trillions of bacteria and other organisms. We need bacteria to synthesise vitamins and digest things, just as much as they need a stomach to thrive in. Nature isn’t something out there, separated behind a wall, it’s connected and ever-present.

Foraging, for me, is really just an approach to making work. It’s anti-production line, pro-wandering. In her text, Reilly described my approach as ‘radical play,’ I like that. I’m really drawn to a lot of New-Topographical photographers: Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Bernd and Hilla Becher. The result is photographic images, but the process is often very sculptural, arrived at by foraging, journeying, collecting. Robert Adam’s Summer Nights, Walking series is a beautiful reference point. It’s about meandering and noticing things, seeing how the headlights from a car can change what a puddle is in the dark. I think it’s important to not force things, let things reveal themselves.